Introduction

The South China Sea (SCS) dispute is a critical geopolitical and legal flashpoint, involving overlapping territorial and maritime claims by six parties: China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Taiwan, and Brunei. This region, a conduit for $3 trillion in annual global trade, holds vast fisheries and estimated hydrocarbon reserves of 11 billion barrels of oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. At the core is China’s expansive “nine-dash line” claim, rooted in historical assertions but deemed unlawful by the 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) ruling, which favored the Philippines. China’s rejection of the ruling, coupled with its artificial island-building, militarization, and harassment of fishing vessels, has escalated tensions, drawing in external powers like the United States and challenging ASEAN’s diplomatic efforts for a binding Code of Conduct (COC). This article analyzes the perspectives of key actors, with an in-depth examination of China’s stance, historical claims, and internal debates, alongside the positions of other claimants, ASEAN, and the U.S.

Overview of the Dispute

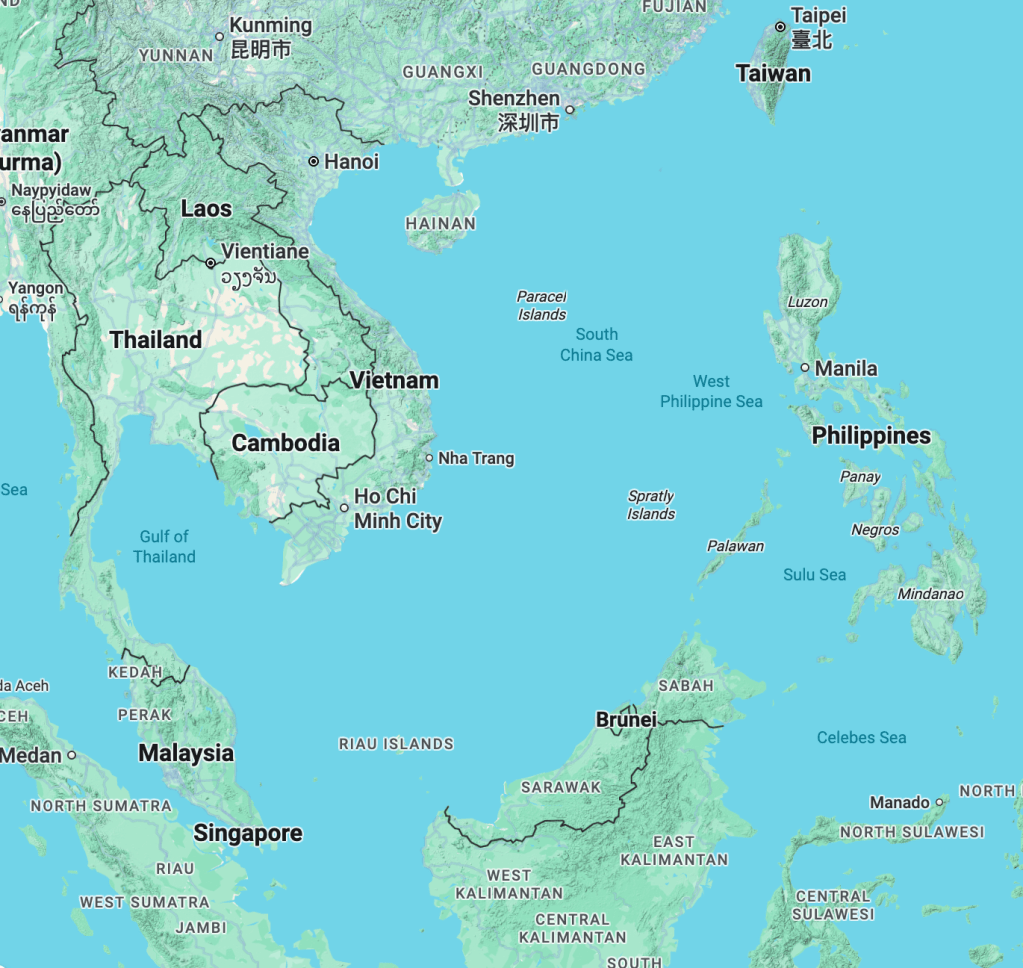

The SCS dispute revolves around sovereignty over the Spratly Islands, Paracel Islands, Pratas Islands, and Scarborough Shoal, as well as maritime rights to resources and navigation. Key flashpoints include Scarborough Shoal (Philippines-China), Second Thomas Shoal (Philippines-China), Vanguard Bank (Vietnam-China), and Luconia Shoals (Malaysia-China), where incidents like vessel ramming, water cannon use, and fishing bans have intensified tensions. The 2016 PCA ruling clarified that many disputed features are rocks or low-tide elevations, not entitled to expansive maritime zones, and invalidated China’s nine-dash line under UNCLOS. Despite this, China’s assertive actions—reclamation, militarization, and coercion—persist, complicating ASEAN’s COC negotiations and drawing U.S. involvement.

The 2016 PCA Ruling

The 2016 PCA ruling (The Republic of the Philippines v. The People’s Republic of China, PCA Case No. 2013-19), issued on July 12, 2016, under UNCLOS Annex VII, addressed 15 Philippine submissions challenging China’s claims and actions. Initiated in 2013 after China’s 2012 seizure of Scarborough Shoal, the 501-page award ruled in favor of the Philippines on nearly all points:

- Nine-Dash Line: China’s claim to “historic rights” within the nine-dash line was ruled incompatible with UNCLOS, which grants coastal states exclusive rights to resources within their 200-nm EEZs. The line, lacking precise legal or geographical basis, was deemed to have no legal effect beyond China’s UNCLOS entitlements.

- Feature Classifications: Under UNCLOS Article 121:

- Scarborough Shoal and Spratly features like Itu Aba (Taiwan), Mischief Reef, and Subi Reef were classified as rocks, entitled only to a 12-nm territorial sea.

- Mischief Reef and Second Thomas Shoal were low-tide elevations, generating no maritime zones unless within 12 nm of a high-tide feature.

- China’s Violations: China breached UNCLOS by:

- Blocking Philippine fishing and resupply missions at Scarborough Shoal and Second Thomas Shoal.

- Causing “severe harm” to coral reefs through reclamation, violating environmental obligations (Articles 192, 194).

- Engaging in unsafe maritime conduct, risking collisions.

- Fishing Rights: Both Filipino and Chinese fishers have traditional fishing rights at Scarborough Shoal.

- Jurisdiction: The PCA rejected China’s claim of non-jurisdiction, as the case concerned maritime entitlements, not sovereignty, and proceeded despite China’s non-participation.

The ruling provided a legal benchmark but lacks enforcement, with China rejecting it as “illegal.”

Perspectives of Key Actors

China

China asserts “indisputable sovereignty” over the SCS within its nine-dash line, claiming nearly 90% of the region, including the Spratlys, Paracels, Scarborough Shoal, and Pratas Islands. Its stance is multifaceted:

- Historical Claims: China’s claims are rooted in historical records from the Han (206 BCE–220 CE), Song (960–1279), and Qing (1644–1912) dynasties, citing maritime exploration, fishing, and administration. Key evidence includes maps like the 13th-century “Da Ming Hunyi Tu” and Qing-era patrols, though these are contested by Vietnam and others for lack of specificity. The 1947 eleven-dash line, formalized by the Republic of China and adopted by the PRC in 2009, underpins these claims, asserting “historical rights” to resources and waters.

- Xi Jinping’s Approach: Under President Xi Jinping (2013–present), China has taken a more assertive stance compared to predecessors Hu Jintao (2003–2013) and Jiang Zemin (1993–2003). Hu emphasized “peaceful development,” engaging in early COC talks and joint ventures, such as with Vietnam in the Gulf of Tonkin. Xi, however, has prioritized “core national interests,” rejecting the 2016 PCA ruling as “null and void” and accelerating militarization. His 2017 speech at the 19th Party Congress framed the SCS as integral to China’s “great rejuvenation,” linking it to national sovereignty. Xi has proposed joint development, as in a 2018 MOU with the Philippines, but insists on bilateral talks, sidelining multilateral forums.

- Actions:

- Artificial Island-Building: Since 2013, China has reclaimed over 3,200 acres across seven Spratly reefs (e.g., Mischief, Subi, Fiery Cross), building airstrips, radar systems, missile batteries, and naval facilities. The PCA ruling deemed these actions environmentally damaging and unlawful within the Philippines’ EEZ.

- Harassment of Fishing Boats: China’s coast guard and maritime militia enforce fishing bans, blockading Filipino fishers at Scarborough Shoal (since 2012) and Vietnamese boats at Vanguard Bank (2019–2025). In 2021, over 200 militia vessels swarmed Whitsun Reef, prompting Philippine protests.

- Diplomatic Pressure: China protests other claimants’ activities, such as Vietnam’s oil exploration, and leverages economic ties to influence ASEAN states like Cambodia.

- Scholarly Perspectives: Some Chinese scholars, like Wu Shicun of the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, advocate softer approaches, such as joint development and confidence-building measures, to reduce tensions and avoid international isolation. Others, like Yan Xuetong, suggest pragmatic negotiations to align with UNCLOS partially, but these views are overshadowed by Xi’s hardline policy, driven by domestic nationalism.

- Compared to Previous Leaders: Jiang Zemin focused on economic integration, avoiding overt SCS conflicts, while Hu Jintao balanced assertiveness with diplomacy. Xi’s approach is more nationalistic, tying SCS control to China’s global rise, with increased military and economic coercion.

China’s actions assert de facto control but risk regional backlash and U.S. intervention.

The Philippines

The Philippines asserts rights within its 200-nm EEZ, including Scarborough Shoal and parts of the Spratlys, grounded in UNCLOS and the 2016 PCA ruling. Its stance has shifted significantly:

- Duterte Administration (2016–2022): President Rodrigo Duterte deprioritized the PCA ruling, calling it a “piece of paper” to secure Chinese investment and trade ($24 billion in pledges). He signed a 2018 MOU for joint oil exploration and allowed Chinese fishing at Scarborough Shoal, despite ongoing harassment. By 2021, continued Chinese blockades at Second Thomas Shoal prompted stronger rhetoric, but Duterte avoided escalation.

- Marcos Administration (2022–Present): President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. has taken a hardline stance, vowing not to cede “one square inch” and leveraging the PCA ruling to challenge China’s “illegal, coercive” actions, such as water cannon use and vessel ramming at Second Thomas Shoal in 2024–2025. Marcos has deepened U.S. ties, securing $500 million in military aid and expanding EDCA bases, while joining multilateral patrols with Japan and Australia. He pushes for a binding COC as ASEAN’s 2026 chair.

- Differences: Duterte’s conciliatory approach prioritized economic benefits and avoided confrontation, while Marcos’ assertive stance, driven by domestic pressure to protect fishing communities and national pride, leverages international law and alliances.

Vietnam

Vietnam claims the Paracel and Spratly Islands, based on historical administration from feudal eras and occupation of 21 Spratly outposts. It relies on UNCLOS, protesting Chinese fishing bans and disruptions at Vanguard Bank, where Chinese vessels have blocked oil exploration since 2019. Hanoi’s “cooperation and struggle” strategy balances trade with China against assertive diplomacy, including threats of legal action. Vietnam has expanded its Spratly outposts, adding 120 acres in 2024–2025, and strengthened ties with the U.S., India, and Japan. Public anti-China sentiment, fueled by incidents like the 2014 Haiyang Shiyou 981 oil rig standoff and vessel sinkings in 2019–2020, pressures Hanoi to adopt a firm stance. Protests in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City reflect strong nationalist support for defending SCS claims, particularly fishing rights critical to coastal communities.

Vietnam pursues a “hedging” strategy, balancing economic ties with China—its largest trading partner at $133 billion in 2023—with assertive diplomacy. It has threatened legal action similar to the Philippines’ 2013 arbitration but prefers multilateral frameworks like ASEAN. Vietnam supports the 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) ruling, which invalidated China’s nine-dash line and affirmed UNCLOS-based EEZ rights, though it has not pursued arbitration itself, preferring diplomatic and multilateral approaches. As ASEAN chair in 2020, Vietnam pushed for COC progress, and in 2025, it supports Malaysia’s efforts to finalize a binding COC by 2026, emphasizing UNCLOS and restraint.

Vietnam has deepened ties with external powers to counterbalance China. In 2023, it upgraded its U.S. partnership to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, securing maritime security aid and joint exercises. Similar partnerships with India, Japan, and Australia include defense cooperation and technology transfers. In 2024, Vietnam hosted U.S. and Japanese naval visits and conducted joint patrols with the Philippines, signaling a shift toward collective security.

Vietnam has bolstered its maritime capabilities, acquiring six Kilo-class submarines from Russia and modernizing its coast guard with U.S. and Japanese support. In 2024–2025, it expanded Spratly outposts by 120 acres, adding radar and defensive structures to counter Chinese militarization. Unlike China’s large-scale reclamation, Vietnam’s efforts are smaller but strategic, aimed at securing its holdings without provoking direct conflict.

Malaysia

Malaysia claims parts of the Spratlys and its EEZ off Sabah and Sarawak, occupying five features like Swallow Reef. Malaysia’s claims are based on its administration of maritime areas, which were part of British colonial territories before Malaysia’s independence in 1957. Historical records, including British surveysand fishing activities, support Malaysia’s presence in the southern Spratlys. Unlike China or Vietnam, Malaysia does not rely heavily on ancient historical claims but emphasizes modern administrative continuity.

Malaysia prioritizes oil and gas exploration at Luconia Shoals, where Chinese harassment disrupted operations like the West Capella field in 2020. Malaysia employs quiet diplomacy, issuing private protests to preserve trade with China ($98.8 billion in 2023). As 2025 ASEAN chair, it accelerates COC talks, emphasizing UNCLOS. Its approach balances economic pragmatism with legal rights. Malaysia supports the 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) ruling, which invalidated China’s nine-dash line and affirmed UNCLOS-based EEZ rights, though it has not pursued arbitration itself, preferring diplomatic channels.

Malaysia occupies five features in the Spratlys: Swallow Reef (Layang-Layang), Ardasier Reef, Mariveles Reef, Erica Reef, and Investigator Shoal. Swallow Reef hosts a naval station, airstrip, and diving resort, reinforcing Malaysia’s effective control. Unlike Vietnam’s 21 outposts or China’s militarized artificial islands, Malaysia’s presence is modest but strategically significant.

Taiwan

Taiwan claims the Spratlys, Paracels, Pratas Islands, and Scarborough Shoal, mirroring China’s nine-dash line but promoting peaceful cooperation via its 2015 South China Sea Peace Initiative. It occupies Itu Aba and Pratas, rejecting the PCA ruling’s classification of Itu Aba as a rock. The Peace Initiative advocates joint resource development and environmental protection. Taiwan’s diplomatic isolation limits COC participation, but it engages with the U.S. and Japan. Chinese incursions near Pratas in 2024–2025 prompted defensive measures.

Brunei

Brunei claims Louisa Reef and its EEZ, based on UNCLOS and a 2009 UN submission, focusing on oil and gas.It avoids public confrontation with China, supporting ASEAN’s COC and UNCLOS. Economic ties, including BRI projects, shape its quiet diplomacy.

ASEAN

ASEAN’s fragmented stance reflects its consensus-based approach, with Cambodia and Laos (non-claimants) aligning with China. It advocates UNCLOS, peaceful resolution, and a COC, building on the 2002 DOC. In 2024–2025, ASEAN noted concerns over Chinese actions at Second Thomas Shoal, urging restraint. Malaysia’s 2025 chairmanship targets COC completion by 2026.

United States

The U.S., a non-claimant, opposes China’s nine-dash line and militarization, endorsing the 2016 PCA ruling and UNCLOS. It conducts FONOPs and joint exercises, particularly with the Philippines under the 1951 MDT, providing $500 million in aid in 2024. Differences between administrations include:

- Trump (2016–2020, 2024-Present): Trump’s unilateral, “America First” approach rejected China’s claims as “unlawful” in 2020, with nine FONOPs in 2019 and dual carrier exercises. Limited ASEAN engagement and TPP withdrawal reduced U.S. influence.

- Biden (2020–2024): Biden’s multilateral approach deepened ASEAN ties and integrated SCS policy into the Indo-Pacific Strategy, with coordinated patrols and Quad/AUKUS frameworks. Concerns about Trump’s second term (starting January 2025) suggest potential reduced multilateral commitment.

Implications and Challenges

- Legal vs. Power Dynamics: The PCA ruling lacks enforcement, enabling China’s actions.

- ASEAN Divisions: China’s influence hinders COC progress.

- Escalation Risks: Incidents like Second Thomas Shoal clashes risk conflict.

- U.S.-China Rivalry: The SCS is a proxy for broader competition.

Policy Recommendations

1. Accelerate and Strengthen ASEAN’s Code of Conduct (COC) Negotiations

Objective: Establish a binding, enforceable framework to manage SCS disputes and prevent escalation.

- Action: ASEAN, under Malaysia’s 2025 chairmanship and the Philippines’ 2026 leadership, should expedite COC negotiations, targeting completion by 2026 with clear, legally binding provisions. The COC should:

- Explicitly reference UNCLOS and the 2016 PCA ruling to anchor maritime rights.

- Include mechanisms for dispute resolution, such as arbitration or joint monitoring committees.

- Prohibit unilateral actions like reclamation or militarization, with sanctions for violations.

- Implementation: ASEAN should form a dedicated working group, led by claimant states (Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia), to draft enforceable clauses, reducing reliance on China-aligned members like Cambodia. External partners, such as Japan and Australia, should provide technical and diplomatic support to strengthen ASEAN’s capacity.

- Rationale: A binding COC would provide a multilateral framework to manage tensions, counter China’s preference for bilateral talks, and reinforce international law, addressing the 2016 ruling’s enforcement gap.

- Challenges: China’s resistance to binding terms and ASEAN’s consensus-based approach may delay progress. Claimant states must align to overcome vetoes by non-claimants like Cambodia.

2. Promote Joint Resource Development Agreements

Objective: Reduce tensions by fostering cooperative exploitation of SCS resources without prejudice to sovereignty claims.

- Action: Claimants should negotiate joint development zones (JDZs) for fisheries, oil, and gas, building on proposals like Taiwan’s South China Sea Peace Initiative and Chinese scholars’ calls for pragmatic cooperation. Key steps include:

- Establishing pilot JDZs in less contentious areas, such as overlapping EEZs near Vanguard Bank or Luconia Shoals.

- Creating joint management bodies with representatives from claimants to oversee resource allocation and environmental protection.

- Leveraging neutral third parties, like Singapore or international organizations, to mediate agreements.

- Implementation: Vietnam and the Philippines, as assertive claimants, should lead bilateral talks with Malaysia and Brunei, potentially including China if it agrees to UNCLOS-based terms. The 2018 Philippines-China MOU on oil exploration could serve as a model, though it requires transparency to avoid sovereignty concessions.

- Rationale: JDZs would de-escalate economic competition, protect fishing communities, and align with Deng Xiaoping’s “shelving disputes, pursuing joint development” concept, while addressing environmental concerns raised in the 2016 PCA ruling.

- Challenges: China’s insistence on bilateral deals and distrust among claimants, particularly Vietnam and the Philippines, may hinder progress. Transparent frameworks and international oversight are critical to build trust.

3. Enhance U.S. and Allied Economic Engagement in ASEAN

Objective: Counter China’s economic influence to bolster ASEAN unity and support claimants’ UNCLOS-based rights.

- Action: The U.S., Japan, Australia, and the EU should expand economic initiatives in ASEAN to reduce reliance on China, which leverages trade ($500 billion with ASEAN in 2023) to influence states like Cambodia and Laos. Recommendations include:

- Launching an Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) with binding trade and investment commitments, focusing on infrastructure and energy projects in claimant states.

- Providing financial and technical support for offshore resource exploration, such as Vietnam’s Blue Whale project or Malaysia’s Luconia Shoals operations.

- Offering capacity-building programs for maritime industries, particularly fishing, to support coastal communities affected by Chinese bans.

- Implementation: The U.S. should leverage the 2022 ASEAN-U.S. Comprehensive Strategic Partnership to fund joint projects, while Japan’s expertise in maritime technology could enhance ASEAN’s coast guard capabilities.

- Rationale: Economic engagement would strengthen ASEAN’s bargaining power in COC talks and reduce China’s ability to divide the bloc, supporting claimants like Vietnam and the Philippines.

- Challenges: U.S. domestic priorities and ASEAN’s diverse economic interests may limit commitment. The incoming Trump administration (January 2025) may prioritize bilateral trade deals, potentially undermining multilateral efforts.

4. Establish Maritime Crisis Management Mechanisms

Objective: Prevent accidental escalations and mitigate risks from incidents like vessel ramming or fishing disputes.

- Action: Claimants and external powers should establish maritime hotlines and incident management protocols, modeled on the 2014 Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES). Specific measures include:

- Creating a claimant-led hotline for real-time communication during maritime incidents, such as those at Second Thomas Shoal or Vanguard Bank.

- Developing a regional maritime monitoring system, using satellite and radar data, to track vessel movements and verify violations.

- Conducting joint search-and-rescue and environmental protection exercises to build trust.

- Implementation: ASEAN should lead, with Vietnam and the Philippines coordinating with the U.S. and Japan to provide technical support. Taiwan’s experience with humanitarian operations at Itu Aba could inform joint exercises.

- Rationale: Crisis management mechanisms would reduce the risk of miscalculations, as seen in 2024 Chinese-Philippine clashes, and foster cooperation without resolving sovereignty disputes.

- Challenges: China’s reluctance to multilateral mechanisms and distrust among claimants may delay implementation. Neutral facilitation by non-claimants like Singapore is essential.

5. Strengthen Regional Maritime Security Cooperation

Objective: Enhance claimants’ capabilities to deter Chinese coercion and protect UNCLOS-based rights.

- Action: The U.S., Japan, Australia, and India should expand maritime security assistance to Vietnam, the Philippines, and Malaysia, focusing on:

- Providing advanced patrol vessels, drones, and radar systems to monitor EEZs and counter Chinese maritime militia.

- Increasing joint exercises, like Balikatan (U.S.-Philippines) and Vietnam’s 2024 patrols with the Philippines, to build interoperability.

- Supporting legal capacity-building for potential arbitration cases, as Vietnam has considered.

- Implementation: The U.S. should expand its $500 million military aid package to the Philippines (2024) to include Vietnam and Malaysia, while Japan’s coast guard training programs could be scaled up. The Quad could coordinate maritime domain awareness initiatives.

- Rationale: Enhanced capabilities would deter Chinese harassment, as seen in 2024–2025 incidents at Second Thomas Shoal, and strengthen claimants’ ability to enforce the 2016 PCA ruling.

- Challenges: China may view increased cooperation as provocation, and claimants’ limited resources require sustained external support.

6. Amplify International Advocacy for UNCLOS and the PCA Ruling

Objective: Increase global pressure on China to comply with international law.

- Action: Claimants and allies should launch a coordinated diplomatic campaign to:

- Highlight China’s violations of the 2016 PCA ruling in UN and ASEAN forums, citing specific incidents like vessel ramming and environmental damage.

- Encourage non-claimant states (e.g., EU, Canada) to issue statements supporting UNCLOS and the PCA ruling.

- Use public diplomacy to raise awareness of Chinese fishing bans’ impact on coastal communities.

- Implementation: The Philippines and Vietnam should lead, leveraging their UN submissions and ASEAN roles, with U.S. and EU support at the UN General Assembly.

- Rationale: Global advocacy would isolate China diplomatically, reinforcing the PCA ruling’s legitimacy and encouraging compliance.

- Challenges: China’s economic influence and veto power at the UN Security Council limit impact, requiring sustained pressure from multiple actors.

Implementation Considerations

- Coordination: ASEAN should establish a task force to align claimant states’ strategies, with neutral facilitators like Singapore ensuring inclusivity.

- Funding: The U.S., Japan, and the EU should allocate $1–2 billion annually for maritime security and economic projects, leveraging existing frameworks like IPEF.

- Timeline: Prioritize COC completion by 2026, with JDZs and hotlines established by 2027 to capitalize on current ASEAN momentum.

- Monitoring: Use satellite imagery and international observers to verify compliance with agreements and document violations.

Risks and Mitigation

- Chinese Resistance: China may escalate actions in response to multilateral pressure. Regular U.S.-ASEAN dialogues can signal unified resolve to deter aggression.

- ASEAN Disunity: Economic dependence on China may weaken ASEAN’s stance. Targeted U.S. and Japanese investments can reduce this leverage.

- U.S. Policy Shifts: The incoming Trump administration (January 2025) may prioritize bilateral deals, undermining multilateral efforts. Engaging ASEAN early in 2025 can lock in commitments.

- Escalation Risks: Joint exercises and FONOPs may provoke China. Clear communication through hotlines and CUES can mitigate miscalculations.

Conclusion

The South China Sea dispute, driven by China’s historical claims and assertive actions under Xi Jinping, challenges UNCLOS-based rights of Southeast Asian claimants. The 2016 PCA ruling remains a legal cornerstone, but China’s non-compliance, island-building, and fishing boat harassment sustain tensions. The Philippines’ shift from Duterte’s conciliation to Marcos’ assertiveness, alongside U.S. policy continuity with Biden’s multilateralism versus Trump’s unilateralism, underscores the dispute’s complexity. ASEAN’s fragmented COC efforts and Taiwan’s constrained role highlight the need for innovative diplomacy. As of August 2025, balancing legal principles, cooperative frameworks, and strategic restraint is critical to prevent escalation and foster stability.

The South China Sea dispute demands a multifaceted approach to de-escalate tensions and uphold international law. Strengthening ASEAN’s COC, promoting joint resource development, enhancing U.S.-led economic engagement, establishing crisis management mechanisms, bolstering maritime security, and amplifying global advocacy for UNCLOS offer a comprehensive strategy. These recommendations address the enforcement gap of the 2016 PCA ruling, counter China’s coercive tactics, and foster cooperation among claimants. As of August 9, 2025, coordinated action by ASEAN, claimants, and external partners like the U.S. is critical to ensure stability in this vital maritime region, balancing deterrence with diplomacy to prevent conflict and secure mutual benefits.

Leave a comment